Internals

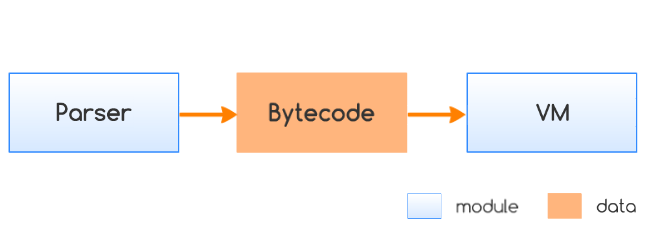

High-Level Design

The diagram above shows the interactions between the major components of JerryScript: Parser and Virtual Machine (VM). Parser performs translation of input ECMAScript application into the byte-code with the specified format (refer to Bytecode and Parser page for details). Prepared bytecode is executed by the Virtual Machine that performs interpretation (refer to Virtual Machine and ECMA pages for details).

Parser

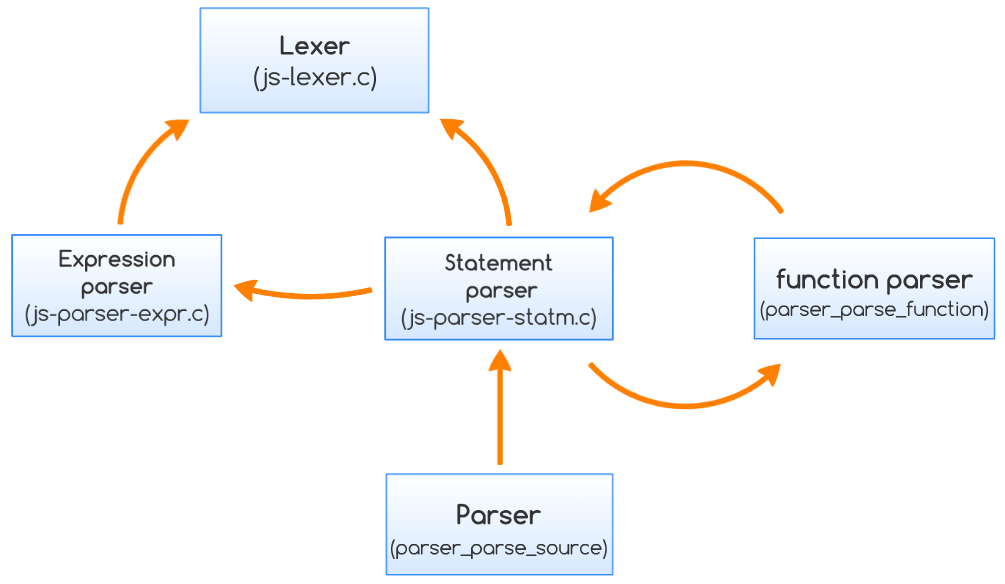

The parser is implemented as a recursive descent parser. The parser converts the JavaScript source code directly into byte-code without building an Abstract Syntax Tree. The parser depends on the following subcomponents.

Lexer

The lexer splits input string (ECMAScript program) into sequence of tokens. It is able to scan the input string not only forward, but it is possible to move to an arbitrary position. The token structure described by structure lexer_token_t in ./jerry-core/parser/js/js-lexer.h.

Scanner

Scanner (./jerry-core/parser/js/js-parser-scanner.c) pre-scans the input string to find certain tokens. For example, scanner determines whether the keyword for defines a general for or a for-in loop. Reading tokens in a while loop is not enough because a slash (/) can indicate the start of a regular expression or can be a division operator.

Expression Parser

Expression parser is responsible for parsing JavaScript expressions. It is implemented in ./jerry-core/parser/js/js-parser-expr.c.

Statement Parser

JavaScript statements are parsed by this component. It uses the Expression parser to parse the constituent expressions. The implementation of Statement parser is located in ./jerry-core/parser/js/js-parser-statm.c.

Function parser_parse_source carries out the parsing and compiling of the input ECMAScript source code. When a function appears in the source parser_parse_source calls parser_parse_function which is responsible for processing the source code of functions recursively including argument parsing and context handling. After the parsing, function parser_post_processing dumps the created opcodes and returns an ecma_compiled_code_t* that points to the compiled bytecode sequence.

The interactions between the major components shown on the following figure.

Byte-code

This section describes the compact byte-code (CBC) representation. The key focus is reducing memory consumption of the byte-code representation without sacrificing considerable performance. Other byte-code representations often focus on performance only so inventing this representation is an original research.

CBC is a CISC like instruction set which assigns shorter instructions for frequent operations. Many instructions represent multiple atomic tasks which reduces the bytecode size. This technique is basically a data compression method.

Compiled Code Format

The memory layout of the compiled bytecode is the following.

The header is a cbc_compiled_code structure with several fields. These fields contain the key properties of the compiled code.

The literals part is an array of ecma values. These values can contain any ECMAScript value types, e.g. strings, numbers, functions and regexp templates. The number of literals is stored in the literal_end field of the header.

CBC instruction list is a sequence of bytecode instructions which represents the compiled code.

Byte-code Format

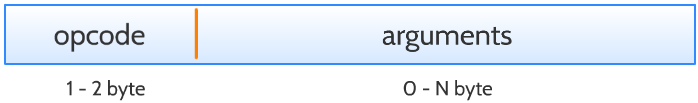

The memory layout of a byte-code is the following:

Each byte-code starts with an opcode. The opcode is one byte long for frequent and two byte long for rare instructions. The first byte of the rare instructions is always zero (CBC_EXT_OPCODE), and the second byte represents the extended opcode. The name of common and rare instructions start with CBC_ and CBC_EXT_ prefix respectively.

The maximum number of opcodes is 511, since 255 common (zero value excluded) and 256 rare instructions can be defined. Currently around 215 frequent and 70 rare instructions are available.

There are three types of bytecode arguments in CBC:

-

byte argument: A value between 0 and 255, which often represents the argument count of call like opcodes (function call, new, eval, etc.).

-

literal argument: An integer index which is greater or equal than zero and less than the

literal_endfield of the header. For further information see next section Literals (next). -

relative branch: An 1-3 byte long offset. The branch argument might also represent the end of an instruction range. For example the branch argument of

CBC_EXT_WITH_CREATE_CONTEXTshows the end of awithstatement. More precisely the position after the last instruction in the with clause.

Argument combinations are limited to the following seven forms:

- no arguments

- a literal argument

- a byte argument

- a branch argument

- a byte and a literal arguments

- two literal arguments

- three literal arguments

Literals

Literals are organized into groups whose represent various literal types. Having these groups consuming less space than assigning flag bits to each literal.

(In the followings, the mentioned ranges represent those indices which are greater than or equal to the left side and less than the right side of the range. For example a range between ident_end and literal_end fields of the byte-code header contains those indices, which are greater than or equal to ident_end

and less than literal_end. If ident_end equals to literal_end the range is empty.)

The two major group of literals are identifiers and values.

-

identifier: A named reference to a variable. Literals between zero and

ident_endof the header belongs to here. All of these literals must be a string or undefined. Undefined can only be used for those literals which cannot be accessed by a literal name. For examplefunction (arg,arg)has two arguments, but theargidentifier only refers to the second argument. In such cases the name of the first argument is undefined. Furthermore optimizations such as CSE may also introduce literals without name. -

value: A reference to an immediate value. Literals between

ident_endandconst_literal_endare constant values such as numbers or strings. These literals can be used directly by the Virtual Machine. Literals betweenconst_literal_endandliteral_endare template literals. A new object needs to be constructed each time when their value is accessed. These literals are functions and regular expressions.

There are two other sub-groups of identifiers. Registers are those identifiers which are stored in the function call stack. Arguments are those registers which are passed by a caller function.

There are two types of literal encoding in CBC. Both are variable length, where the length is one or two byte long.

- small: maximum 511 literals can be encoded.

One byte encoding for literals 0 - 254.

byte[0] = literal_index

Two byte encoding for literals 255 - 510.

byte[0] = 0xff

byte[1] = literal_index - 0xff

- full: maximum 32767 literal can be encoded.

One byte encoding for literals 0 - 127.

byte[0] = literal_index

Two byte encoding for literals 128 - 32767.

byte[0] = (literal_index >> 8) | 0x80

byte[1] = (literal_index & 0xff)

Since most functions require less than 255 literal, small encoding provides a single byte literal index for all literals. Small encoding consumes less space than full encoding, but it has a limited range.

Literal Store

JerryScript does not have a global string table for literals, but stores them into the Literal Store. During the parsing phase, when a new literal appears with the same identifier that has already occurred before, the string won’t be stored once again, but the identifier in the Literal Store will be used. If a new literal is not in the Literal Store yet, it will be inserted.

Byte-code Categories

Byte-codes can be placed into four main categories.

Push Byte-codes

Byte-codes of this category serve for placing objects onto the stack. As there are many instructions representing multiple atomic tasks in CBC, there are also many instructions for pushing objects onto the stack according to the number and the type of the arguments. The following table list a few of these opcodes with a brief description.

| byte-code | description |

| CBC_PUSH_LITERAL | Pushes the value of the given literal argument. |

| CBC_PUSH_TWO_LITERALS | Pushes the values of the given two literal arguments. |

| CBC_PUSH_UNDEFINED | Pushes an undefined value. |

| CBC_PUSH_TRUE | Pushes a logical true. |

| CBC_PUSH_PROP_LITERAL | Pushes a property whose base object is popped from the stack, and the property name is passed as a literal argument. |

Call Byte-codes

The byte-codes of this category perform calls in different ways.

| byte-code | description |

| CBC_CALL0 | Calls a function without arguments. The return value won’t be pushed onto the stack. |

| CBC_CALL1 | Calls a function with one argument. The return value won’t be pushed onto the stack. |

| CBC_CALL | Calls a function with n arguments. n is passed as a byte argument. The return value won’t be pushed onto the stack. |

| CBC_CALL0_PUSH_RESULT | Calls a function without arguments. The return value will be pushed onto the stack. |

| CBC_CALL1_PUSH_RESULT | Calls a function with one argument. The return value will be pushed onto the stack. |

| CBC_CALL2_PROP | Calls a property function with two arguments. The base object, the property name, and the two arguments are on the stack. |

Arithmetic, Logical, Bitwise and Assignment Byte-codes

The opcodes of this category perform arithmetic, logical, bitwise and assignment operations.

| byte-code | description |

| CBC_LOGICAL_NOT | Negates the logical value that popped from the stack. The result is pushed onto the stack. |

| CBC_LOGICAL_NOT_LITERAL | Negates the logical value that given in literal argument. The result is pushed onto the stack. |

| CBC_ADD | Adds two values that are popped from the stack. The result is pushed onto the stack. |

| CBC_ADD_RIGHT_LITERAL | Adds two values. The left one popped from the stack, the right one is given as literal argument. |

| CBC_ADD_TWO_LITERALS | Adds two values. Both are given as literal arguments. |

| CBC_ASSIGN | Assigns a value to a property. It has three arguments: base object, property name, value to assign. |

| CBC_ASSIGN_PUSH_RESULT | Assigns a value to a property. It has three arguments: base object, property name, value to assign. The result will be pushed onto the stack. |

Branch Byte-codes

Branch byte-codes are used to perform conditional and unconditional jumps in the byte-code. The arguments of these instructions are 1-3 byte long relative offsets. The number of bytes is part of the opcode, so each byte-code with a branch argument has three forms. The direction (forward, backward) is also defined by the opcode since the offset is an unsigned value. Thus, certain branch instructions has six forms. Some examples can be found in the following table.

| byte-code | description |

| CBC_JUMP_FORWARD | Jumps forward by the 1 byte long relative offset argument. |

| CBC_JUMP_FORWARD_2 | Jumps forward by the 2 byte long relative offset argument. |

| CBC_JUMP_FORWARD_3 | Jumps forward by the 3 byte long relative offset argument. |

| CBC_JUMP_BACKWARD | Jumps backward by the 1 byte long relative offset argument. |

| CBC_JUMP_BACKWARD_2 | Jumps backward by the 2 byte long relative offset argument. |

| CBC_JUMP_BACKWARD_3 | Jumps backward by the 3 byte long relative offset argument. |

| CBC_BRANCH_IF_TRUE_FORWARD | Jumps forward if the value on the top of the stack is true by the 1 byte long relative offset argument. |

Snapshot

The compiled byte-code can be saved into a snapshot, which also can be loaded back for execution. Directly executing the snapshot saves the costs of parsing the source in terms of memory consumption and performance. The snapshot can also be executed from ROM, in which case the overhead of loading it into the memory can also be saved.

Virtual Machine

Virtual machine is an interpreter which executes byte-code instructions one by one. The function that starts the interpretation is vm_run in ./jerry-core/vm/vm.c. vm_loop is the main loop of the virtual machine, which has the peculiarity that it is non-recursive. This means that in case of function calls it does not calls itself recursively but returns, which has the benefit that it does not burdens the stack as a recursive implementation.

ECMA

ECMA component of the engine is responsible for the following notions:

- Data representation

- Runtime representation

- Garbage collection (GC)

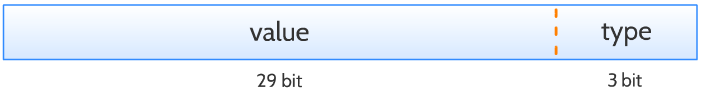

Data Representation

The major structure for data representation is ECMA_value. The lower three bits of this structure encode value tag, which determines the type of the value:

- simple

- number

- string

- object

- symbol

- error

In case of number, string and object the value contains an encoded pointer, and simple value is a pre-defined constant which can be:

- undefined

- null

- true

- false

- empty (uninitialized value)

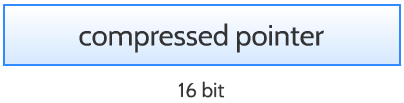

Compressed Pointers

Compressed pointers were introduced to save heap space.

These pointers are 8 byte aligned 16 bit long pointers which can address 512 Kb of memory which is also the maximum size of the JerryScript heap. To support even more memory the size of compressed pointers can be extended to 32 bit to cover the entire address space of a 32 bit system by passing “–cpointer_32_bit on” to the build system. These “uncompressed pointers” increases the memory consumption by around 20%.

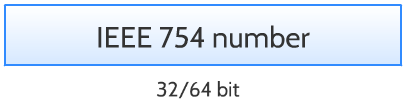

Number

There are two possible representation of numbers according to standard IEEE 754: The default is 8-byte (double), but the engine supports the 4-byte (single precision) representation by setting JERRY_NUMBER_TYPE_FLOAT64 to 0 as well.

Several references to single allocated number are not supported. Each reference holds its own copy of a number.

String

Strings in JerryScript are not just character sequences, but can hold numbers and so-called magic ids too. For common character sequences (defined in ./jerry-core/lit/lit-magic-strings.ini) there is a table in the read only memory that contains magic id and character sequence pairs. If a string is already in this table, the magic id of its string is stored, not the character sequence itself. Using numbers speeds up the property access. These techniques save memory.

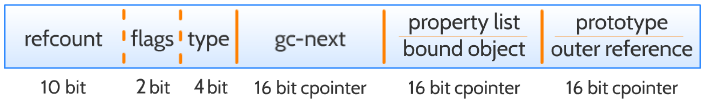

Object / Lexical Environment

An object can be a conventional data object or a lexical environment object. Unlike other data types, object can have references (called properties) to other data types. Because of circular references, reference counting is not always enough to determine dead objects. Hence a chain list is formed from all existing objects, which can be used to find unreferenced objects during garbage collection. The gc-next pointer of each object shows the next allocated object in the chain list.

Lexical environments are implemented as objects in JerryScript, since lexical environments contains key-value pairs (called bindings) like objects. This simplifies the implementation and reduces code size.

The objects are represented as following structure:

- Reference counter - number of hard (non-property) references

- Next object pointer for the garbage collector

- type (function object, lexical environment, etc.)

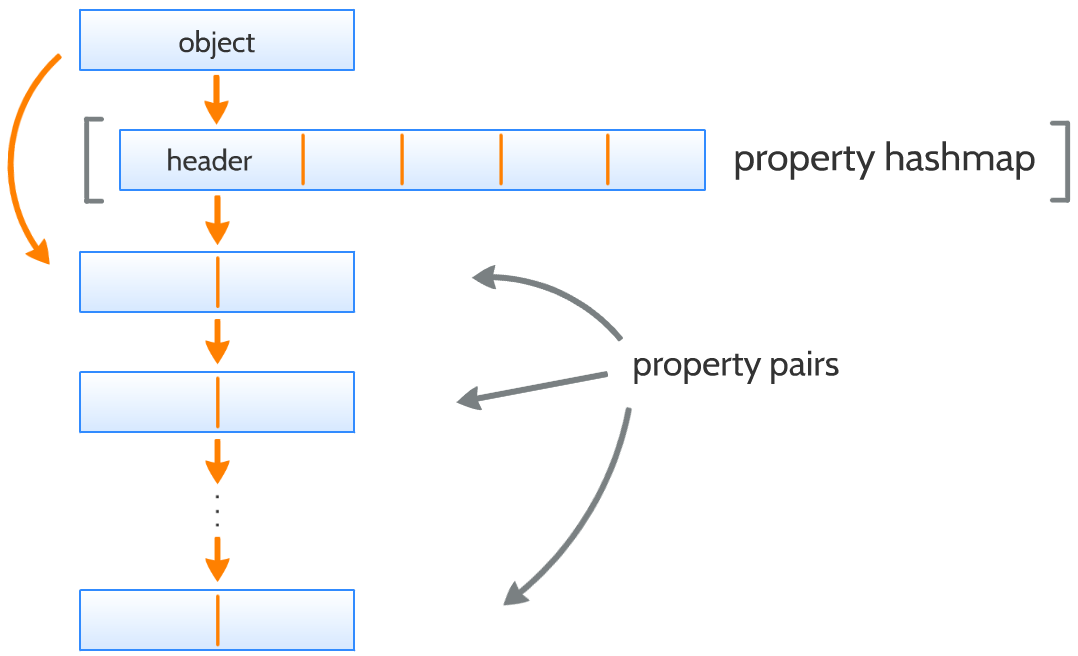

Properties of Objects

Objects have a linked list that contains their properties. This list actually contains property pairs, in order to save memory described in the followings: A property has a one byte long descriptor, a two byte long name and four byte long value. Hence 14 bytes consumed by a property pair. Another two bytes is used to show the next property pair, so the total size (16 byte) is divisible by 8.

Property Hashmap

If the number of property pairs reach a limit (currently this limit is defined to 16), a hash map (called Property Hashmap) is inserted at the first position of the property pair list, in order to find a property using it, instead of finding it by iterating linearly over the property pairs.

Property hashmap contains 2n elements, where 2n is larger than the number of properties of the object. Each element can have tree types of value:

- null, indicating an empty element

- deleted, indicating a deleted property, or

- reference to the existing property

This hashmap is a must-return type cache, meaning that every property that the object have, can be found using it.

Internal Properties

Internal properties are special properties that carry meta-information that cannot be accessed by the JavaScript code, but important for the engine itself. Some examples of internal properties are listed below:

- [[Class]] - class (type) of the object (ECMA-defined)

- [[Code]] - points where to find bytecode of the function

- native code - points where to find the code of a native function

- [[PrimitiveValue]] for Boolean - stores the boolean value of a Boolean object

- [[PrimitiveValue]] for Number - stores the numeric value of a Number object

LCache

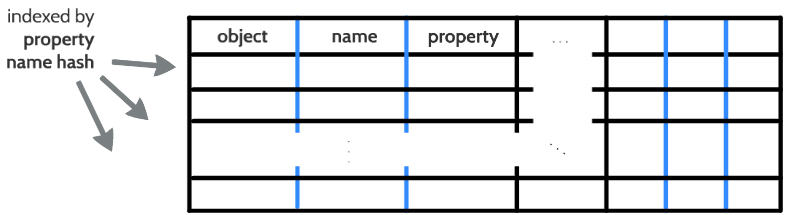

LCache is a hashmap for finding a property specified by an object and by a property name. The object-name-property layout of the LCache presents multiple times in a row as it is shown in the figure below.

When a property access occurs, a hash value is extracted from the demanded property name and than this hash is used to index the LCache. After that, in the indexed row the specified object and property name will be searched.

It is important to note, that if the specified property is not found in the LCache, it does not mean that it does not exist (i.e. LCache is a may-return cache). If the property is not found, it will be searched in the property-list of the object, and if it is found there, the property will be placed into the LCache.

Collections

Collections are array-like data structures, which are optimized to save memory. Actually, a collection is a linked list whose elements are not single elements, but arrays which can contain multiple elements.

Exception Handling

In order to implement a sense of exception handling, the return values of JerryScript functions are able to indicate their faulty or “exceptional” operation. The return values are ECMA values (see section Data Representation) and if an erroneous operation occurred the ECMA_VALUE_ERROR simple value is returned.

Value Management and Ownership

Every ECMA value stored by the engine is associated with a virtual “ownership”, that defines how to manage the value: when to free it when it is not needed anymore and how to pass the value to an other function.

Initially, value is allocated by its owner (i.e. with ownership). The owner has the responsibility for freeing the allocated value. When the value is passed to a function as an argument, the ownership of it will not pass, the called function have to make an own copy of the value. However, as long as a function returns a value, the ownership will pass, thus the caller will be responsible for freeing it.